History of the Lincoln Memorial

Lincoln Memorial under construction, c. 1917. Credit: Library of Congress

Abraham Lincoln (1809-1865) was the 16th president of the United States; he guided the nation through the Civil War, preserved the union of the states, and freed the slaves. In recognition of the magnitude of his reputation and his role in American history, this memorial occupies a site equal in importance to that of the Washington Monument. It was constructed between 1914 and 1922 on the National Mall in Washington, D.C., on land that was reclaimed from the Potomac River at the end of the 19th century.

Architectually speaking, the memorial is in the form of a classical temple, combining elements of Greek and Roman architecture. The exterior is constructed of an ultra-white marble from Colorado. There are 36 Doric columns, 44 feet in height--one for each state in the Union at the time of Lincoln's death. Above each column is the name of a state. Inside the entrance are two additional columns. On the attic wall, outside, are the names of each of the 48 states in the Union when the memorial was completed. The lower steps are granite, while the upper ones are made of marble.

The columns tilt inward slightly, an architectural "refinement," first used in ancient Greece, that lends the memorial an appearance of geometrical perfection. The exterior walls are tilted inward to a lesser degree.

Design and Construction

The area that is now occupied by the Lincoln Memorial and the reflecting pool was originally a part of the Potomac River. In the 1880s and '90s, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers filled it in with silt pumped from the river channel, creating about 600 acres of new land. By the turn of the 20th century, the area was an unfinished wasteland, covered with weeds and brush. At that time, the U.S. Senate appointed a commission to create a plan for for the development of the city's parklands. It was known as the McMillan Commission after Senator James McMillan, its chief sponsor.

Looking west from the Washington Monument toward the the site of the Lincoln Memorial in 1899. Credit: National Archives.

The McMillan Commission presented its plan to Congress in 1902. It proposed extending the National Mall westward through the newly made land to the Potomac, where a memorial to Lincoln would terminate the Mall on the river bank. At the time, there was no significant memorial to Lincoln anywhere in the city, although he had been dead for nearly four decades.

The McMillan Commission comprised four members, but the orginal conception for the memorial and the reflecting pool were largely the work of just one of its members, architect Charles McKim. He envisioned the memorial as an open group of columns, surrounded by a traffic circle with tree-lined avenues radiating outward, similar to the Arc de Triomphe in Paris. (At the time, there was only a handful of automobiles in the city.) A bronze statue of Lincoln would stand in front of the colonnade.

The Lincoln Memorial and the reflecting pool were first proposed by the McMillan Commission in 1902. Credit: Commission of Fine Arts.

Construction of the memorial was set in motion in 1911, when Congress created the Lincoln Memorial Commission and charged it with selecting a site, an architect, and a design. Ultimately, the commission chose the present site on the Potomac, as recommended by the McMillan Commission. Architects Henry Bacon (1866-1924) and John Russell Pope (who later designed the Jefferson Memorial and the National Gallery of Art) each submitted designs, and Bacon's scheme was accepted in 1912.

Architect John Russell Pope suggested this pyramid as one of several alternative schemes for the Lincoln Memorial, 1912. The artwork is thought to be the work of Rockwell Kent. Credit: Commission of Fine Arts.

Bacon's plan called for a Doric temple similar to the Parthenon in Athens, with the long side facing the Mall. Instead of a Greek-style pediment, he proposed a Roman-style attic. A statue of Lincoln would be ensconced in a large room in the interior. Bacon, a protégé of Charles McKim, specialized in designing monuments and memorials, although his work is not well represented in Washington. The Lincoln Memorial is his greatest masterpiece.

Work on the foundations began in 1914. Steel tubes were driven to bedrock, about 50 feet below the surface, and filled with concrete. An upper foundation was made of reinforced concrete. The superstructure, built entirely of stone, was begun in 1915 and completed in 1917. In the following years, the interior, terraces, and approaches were completed. The memorial opened to the public in June 1921, and the dedication was held on Memorial Day 1922. The reflecting pool was completed soon thereafter.

Groundbreaking for the Lincoln Memorial, 1914. The man with the shovel is Col. William Harts of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, which oversaw construction. Just to the right is the architect, Henry Bacon. Credit: Library of Congress.

Statue of Abraham Lincoln

Architect Bacon and the Lincoln Memorial Commission selected Daniel Chester French, the most highly regarded American sculptor of his day, and Bacon's personal friend, to create the statue of Lincoln. French was commissioned in December 1915, but he had already set to work on a series of models. Although the statue was originally planned to be about 10 feet in height, when Bacon and French placed a full-sized model in the atrium, it was dwarfed by the monument's Herculean proportions. With enlarged photographs, they determined that 19 feet would be the proper height.

French provided a scale model to a stone-carving firm, which cut the statue from 28 blocks of white marble from Georgia. The cutting began in 1918, and assembly of the statue was completed in 1920.

Abraham Lincoln is French's masterwork and is probably the best-known sculpture by any American artist. Lincoln is sitting in a large chair, his body relaxed. His face and hands express his intensity, strength, and dedication to purpose. Draped over the chair is an American flag. The entire work radiates a weighty majesty.

The statue is situated against the center of the west wall in a large room, which is divided into three parts by two rows of Ionic columns made of Indiana limestone. The walls are the same material; the floor is pink Tennessee marble. The room is lit from above by a skylight with translucent marble panels in a bronze frame, supplemented by electric lights. Lincoln's "Gettysburg Address" is carved into the south wall; above it is Emancipation, a mural by Jules Guérin. On the north wall is Reunion, also by Guérin, and Lincoln's "Second Inaugural Address."

Reflecting Pool

The reflecting pool in front of the memorial was originally designed to be cruciform, but some wartime temporary buildings then facing Constitution Avenue were in the way, and the pool was built as a rectangle instead. To its east is the smaller Rainbow Pool, so named because an array of water jets, activated on special occasions, created a rainbow effect. In 2001, the Rainbow Pool was demolished to make way for the National World War II Memorial. The pool was reconstructed, in modified form, and incorporated into the new memorial.

Construction of the reflecting pool at the Lincoln Memorial, c. 1921. Credit: Library of Congress.

Symbol of Civil Rights

The memorial to Lincoln, the Great Emancipator, was a potent symbol for the Civil Rights movement. In 1939, the renowned contralto Marian Anderson was denied the use of Constitution Hall in Washington, D.C., because of her race. First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt arranged for her to perform at the Lincoln Memorial instead, and on Easter Sunday 1939, she sang before a crowd of 75,000 on the steps of the memorial. Her performance, broadcast live on national radio, remains one of the defining moments of the Civil Rights movement.

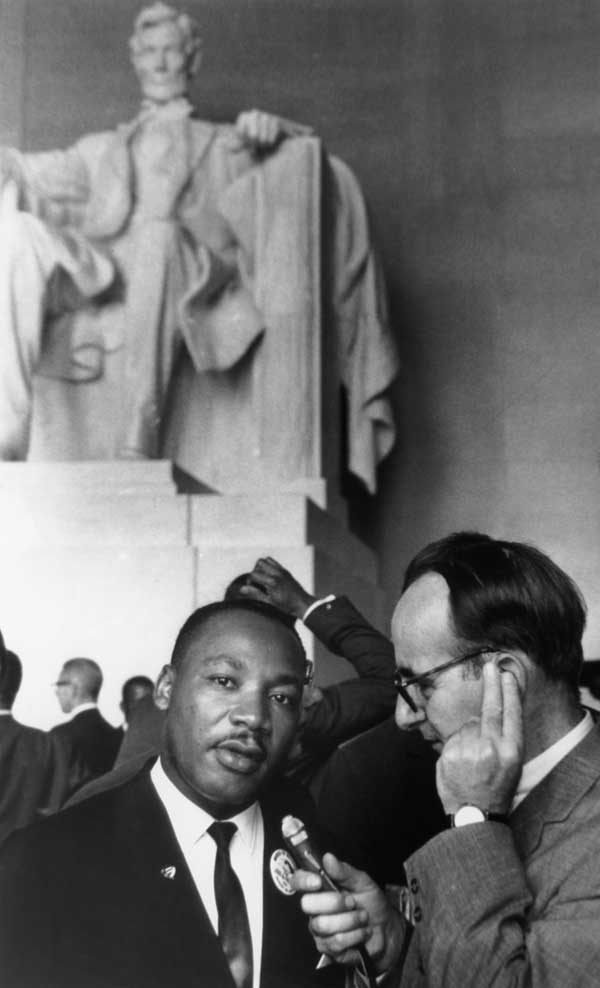

On August 28, 1963, Martin Luther King Jr. delivered his "I Have a Dream" speech from the memorial's steps. The speech was the climax of his March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. The event was organized by a coalition of Civil Rights groups and labor unions. Its purpose was to add momentum to the national push for Civil Rights legislation and to encourage the creation of a large-scale jobs program.

The attention that the march drew from the president and the media would be almost inconceivable today. Working in close cooperation with the Kennedy administration, the march's organizers decided to confine the event to the National Mall. Participants would assemble at the Washington Monument and march in two groups down Constitution and Independence avenues to the Lincoln Memorial. Besides the practical considerations of managing such a large crowd, marching past the White House or the Capitol was perceived as being too confrontational. To have the desired impact, the organizers hoped to have at least 100,000 participants, and toward that goal, they staged a national advertising campaign.

On the day of the march, the participants numbered more than 200,000. The event was broadcast live on television all over the world. The Washington Post estimated that the crowd was 70 percent black and commended the order and dignity of the marchers. At the Washington Monument, participants picked up preprinted signs as entertainers performed on a stage; Joan Baez sang "We Shall Overcome."

After the crowd had moved to the Lincoln Memorial, Marian Anderson began the program by singing the national anthem. The organizers of the march addressed the demonstrators in turn. Other speakers included Rosa Parks and Myrlie Evers, the widow of Medgar Evers. The climax came at the end when King gave his now-immortal speech. He was supposed to talk for only four minutes, but he abandoned his prepared text and spoke for 16 minutes. With his powerful oratory, the 34-year-old Baptist minister articulated his dream to the huge crowd: "I still have a dream. It is a dream deeply rooted in the American dream. I have a dream that one day this nation will rise up and live out the true meaning of its creed: 'We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal.'"

Martin Luther King Jr. being interviewed at the Lincoln Memorial on the day of his "I Have a Dream" speech in 1963. Credit: National Archives.

The March on Washington became the most famous demonstration in American history. The spot where King delivered his speech is now marked by an inscription on the steps of the memorial. "I Have a Dream" is inscribed into the granite on the landing just below the columns, in the center of the steps.

Adapted with permission from The Washington National Mall, by Peter R. Penczer, Oneonta Press, Arlington, Va.: 2007.

Copyright © Peter R. Penczer 2015-16