History of the Washington Monument

George Washington (1732-1799) was the commander of the American armies in the Revolutionary War, presided over the Constitutional Convention in 1787, and was the first president of the United States. His character was regarded as beyond reproach. During his life he was venerated; after his death he was virtually deified.

In 1783, the Continental Congress resolved that an equestrian statue of Washington be erected in the nation's permanent capital. When Peter Charles L'Enfant drew up a plan for the new city in 1791, he provided a site for the statue where the axes of the "Congress House" and the "President's House" intersected. The statue was never realized, but the site was later used for the Washington Monument.

Robert Mills's original design for the Washington Monument called for a 600-foot-tall obelisk surrounded by a pantheon 250 feet in diameter. The pantheon was never built. Credit: National Archives.

In the decades to follow, there were numerous attempts to establish a monument to Washington in the new capital. In 1833 a group of citizens formed the Washington National Monument Society to provide a proper monument to the first president. The society held a design competition in 1836, but none of the entries was acceptable. In 1845, the society adopted a design by architect Robert Mills. The scheme called for a 600-foot obelisk surrounded by a pantheon, 100 feet high and 250 feet in diameter. The monument would be decorated with statues, historical paintings, and bas-relief sculpture. Immense, ornate, and destined to be the tallest building in the world, the society saw the monument as commensurate with the stature of Washington and the American nation. By 1848, enough money had been collected to begin work, and Congress authorized the society to use the site specified by L'Enfant. To save money, the obelisk would be built first, and the pantheon, later.

Presumably because of poor soil conditions, the monument was built somewhat to the southeast of L'Enfant's site, a decision that would have repercussions later, when the Mall was extended westward. Mills was hired to supervise construction, and excavations were completed early in 1848. On July 4, 1848, the cornerstone was laid in a grand ceremony. Present were President James K. Polk, many members of Congress and other dignitaries, U.S. Marines, militia and fire companies, and perhaps 20,000 spectators, including a contingent of aged Revolutionary War veterans. Perched on a decorated arch was an eagle that had witnessed Lafayette's triumphant return to America 24 years earlier.

The foundations and the interior of the shaft were constructed of gneiss; the exterior, of white marble from a quarry near the town of Texas, Maryland. The society received decorative memorial stones from all over the world, which were installed in the interior, facing the stairwell. Stones were contributed by states, territories, foreign countries, fraternal organizations, and many other sources. There are about 200 stones in all, some installed after the completion of the monument.

In 1854, the society ran out of money, and progress on the shaft stopped at 152 feet. That same year, members of the nativist and anti-Catholic Know-Nothing party stole a stone given by the Vatican and reportedly dumped it into the Potomac River. In February 1855 the party seized control of the Washington National Monument Society. During the three years that they controlled the society, the Know-Nothings added only four feet to the obelisk, and the work was of such low quality that the stones were later removed. Progress on the monument stalled at the 156-foot level, and it would remain an unsightly stump for more than 20 years.

In July 1876, in celebration of the nation's centennial, Congress appropriated funds for the completion of the monument. Control of the stump passed from the society to the federal government, and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers was charged with its completion. Work resumed in 1878, with Lieutenant Colonel Thomas Lincoln Casey directing the project.

Washington Monument, 1879. Construction stopped at the 156-foot level for more than 20 years. When work resumed, the original stone foundations, seen here, had to be reinforced with concrete. Credit: Library of Congress.

Casey found the 1848 foundations woefully inadequate and reinforced them with concrete, a delicate operation. The new foundations rest on a firm bed of sand, gravel, and clay, but they do not extend to bedrock. When work resumed, the finished height of the shaft was still in question. George Perkins Marsh, the U.S. minister to Italy, suggested that the proper height should be 10 times the width of the base, a proportion derived from close examination of Egyptian obelisks in Rome. Casey adopted Marsh's suggestions, and the finished height of the monument is 555 feet 5-1/8 inches.

Work resumed on the shaft in August 1880. Initially, Casey used white marble from Sheffield, Massachusetts, for the exterior, but after only a few courses, he switched to marble from Cockeysville, Maryland. The Cockeysville marble is a slightly different color, easily perceptible today. For the interior of the shaft, he used granite from Maine. Work proceeded rapidly, and by August 1884, the shaft had reached the 500-foot level.

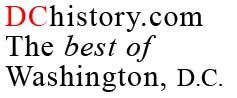

The capstone before it was set in place at the top of the monument. Credit: Library of Congress.

On December 6, 1884, Casey set the 3,300-pound capstone, completing the monument. A small ceremony marked the occasion. At the tip of the capstone was a 100-ounce pyramid of pure aluminum. In 1884, refining and casting pure aluminum was very difficult, and this was the largest such casting of its time. The pyramid was intended as a lightning conductor, but it was soon supplemented with an array of copper rods.

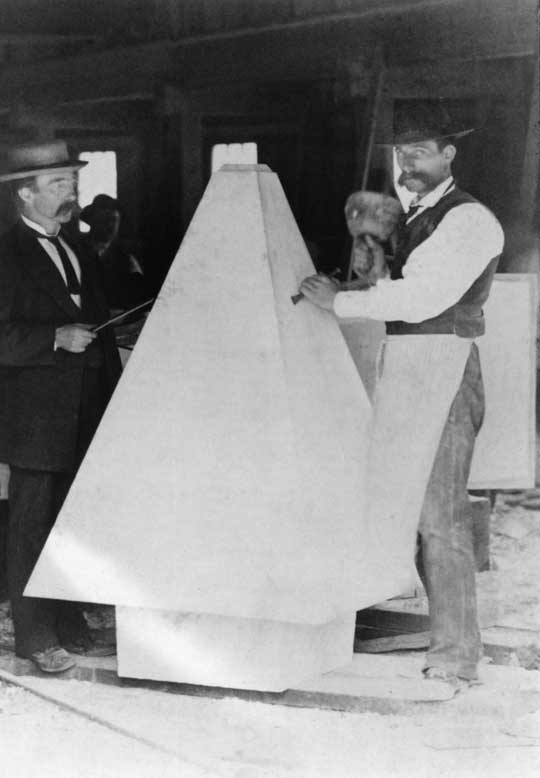

The Washington Monument was dedicated on a frigid day in February, 1885. Credit: Library of Congress.

The Washington Monument was dedicated on February 21, 1885. It was the tallest building in the world, surpassing Cologne Cathedral in Germany. Within five years, the monument was itself surpassed by the Eiffel Tower, but it remains the tallest stone structure in the world.

The Washington Monument, c. 1900. The lodge in the foreground was completed in 1889, and is now a bookshop. Credit: National Archives.

The monument was officially opened to the public in 1888. Visitors could ascend the shaft by traveling in a steam-driven elevator or by climbing the 896 steps. In 1901, the elevator was replaced with one powered by electricity. At the 500-foot level there is an observation platform with eight openings that offer an excellent view of the city. In the 1920s, after several suicides, the openings were fitted with bars, and bulletproof glass was installed in 1974. The stairs were closed to the public in the 1970s.

Between 1998 and 2001, the monument underwent a thorough restoration. Elaborate scaffolding, designed by architect Michael Graves, encased the obelisk for more than a year while the exterior was cleaned and the stonework was repaired. Inside, the memorial stones were restored, the observation deck was refurbished, and a new elevator was installed.

In 1998, in the wake of terrorist attacks on two American embassies in Africa, the National Park Service installed a ring of Jersey barriers around the monument, which remained for five years. In 2005, work was completed on a permanent vehicle barrier, a ring of low granite walls about 400 feet from the shaft. At the same time, the monument grounds were improved with new grading, paths, lighting, benches, and trees. A temporary shed for screening visitors, erected in 2001, is still in place against the base of the monument. As of 2106, plans were in the works for a more attractive, and permanent, facility in the same location, but made of reinforced glass.

On August 23, 2011, a magnitude 5.8 earthquake struck Washington, D.C.; the epicenter was 90 miles southwest of the city near Mineral, Virginia. Because of its height and stone construction, the monument suffered some of the worst damage to any structure in the city, but no one was injured. The marble was spalled and cracked, primarily in the pyramid-shaped summit. The National Park Service was forced to close the monument for nearly three years, erect scaffolding, and effect repairs that cost $15 million.

Adapted with permission from The Washington National Mall, by Peter R. Penczer, Oneonta Press, Arlington, Va.: 2007.

Copyright © Peter R. Penczer 2016